Taxonomy: Ailuropoda melanoleuca [David 1869]: The giant panda was originally brought to the attention of science by Père Armand David, a French Catholic priest with a strong interest in natural history, who traveled widely in China and Mongolia and collected numerous zoological and botanical specimens. He had heard about a black and white bear from local people, and had seen a skin. He obtained two specimens, and named it Ursus melanoleucus (black and white bear). [See separate page: Discovering and Naming Bear Species for Science.] But when the skin and skull was received at a museum in Paris, it was renamed Ailuropoda, meaning “panda foot”, because it appreared similar to the previously discovered red panda. The red panda was once thought to be in the raccoon family, but is now considered a family of its own (Ailuridae), and there are now considered to be two species (Ailurus fulgens and A. styani). The shared morphological traits between the giant and red (lesser) pandas likely arose through convergent evolution, as they are both adapted to a specialized bamboo diet. The giant panda’s membership in the bear family is supported by abundant genetic evidence, and is no longer debated. Notably, it has only 42 chromosomes, versus 74 for ursine bears, but the Andean bear also has fewer chromosomes (52) and is clearly a real bear.

The giant panda diverged within the bear family early during its evolutionary history, branching off some 8 million years ago during the Miocene. It appears that it evolved through multiple chronospecies (one evolving into another, rather than multiple species occurring at once). Present giant panda populations all belong to a single species, although three distinct populations are recognized due to genetic differences: Qinling mountains, the Minshan mountains, and a third, highly fragmented population spread over the Qionglai, Daxiangling, Xiaoxiangling, and Liangshan mountains. Debate exists as to whether the Qinling population is genetically distinct enough to be considered a subspecies (most think it is not).

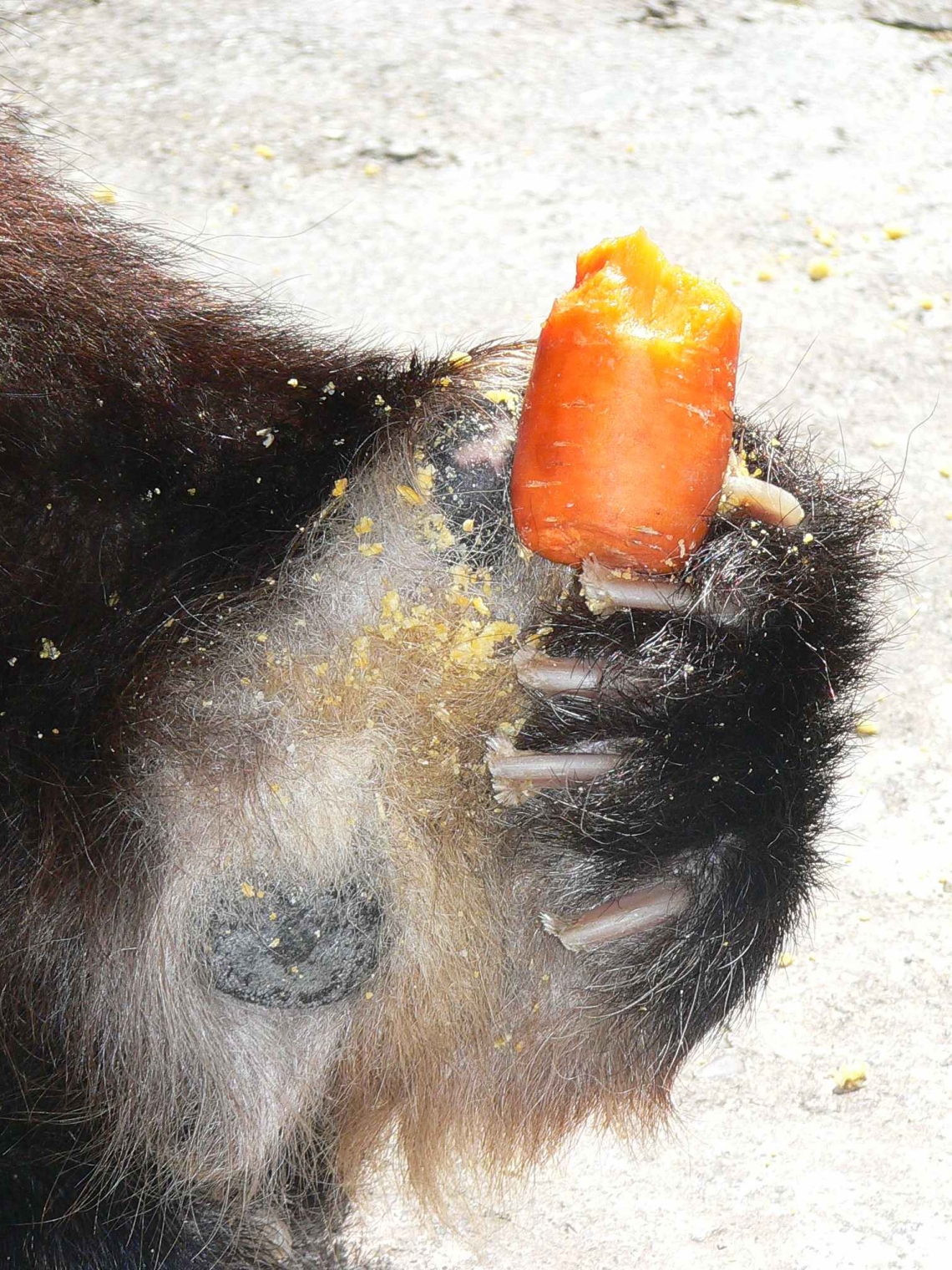

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wolong breeding center Sichaun China_panda holding carrot using pseudo-thumb_D Garshelis

Red panda_Ailurus styani_wild Wolong China_D Garshelis

Distinctive characteristics: This is a medium-sized bear with a distinctive black and white pelage that appears to function as camouflage in the dark and light patterns created by snow and patchy shade in their forested habitat. Giant pandas, unlike other bears that hibernate, remain active when the ground is snow covered, so it is theorized that this made the white coloration adaptive. The black eye patches and ears appear to be used in communication, signaling identity and aggressiveness. Due to its specialized diet of fibrous bamboo, pandas have evolved powerful jaw muscles and supporting bone structure, massive wide crushing teeth, and a unique and interesting “pseudo-thumb,” a modified wrist bone that allows the panda to grasp bamboo during foraging (the bone is opposable against the other 5 digits, creating a seemingly 6th digit).

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_black eye patches black ears _IOZCAS

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_black and white pelage develops at an early age_IOZCAS

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Huangbaiyuan NR_rounded body shape_Fang Wang

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_camera trap China_short rounded face black legs_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_camera trap China_longest tail of any bear species_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wolong breeding center_haired underside of rear foot_D Garshelis

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_full skeleton showing especially large head_D Garshelis.JPG

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_skull showing wide grinding molars_D Garshelis.JPG

Distinctive behaviors: This species is solitary, occupying overlapping ranges with a few other pandas, but interacting infrequently outside of the mating season. They rely heavily on scent for communicating identity, sex, reproductive condition, and other social and reproductive functions. They possess a specialized gland in the anogenital area that creates a waxy substance that they rub on trees, often at communal marking sites where several pandas visit to leave and investigate these signals. They spend more than half of their time foraging on bamboo, an abundant resource with low nutritional value that is quickly passed through the digestive system. As a consequence, they are known to defecate approximately 50 times per day. They climb trees, but not to feed there, and are not as adept at tree climbing as several other bear species.

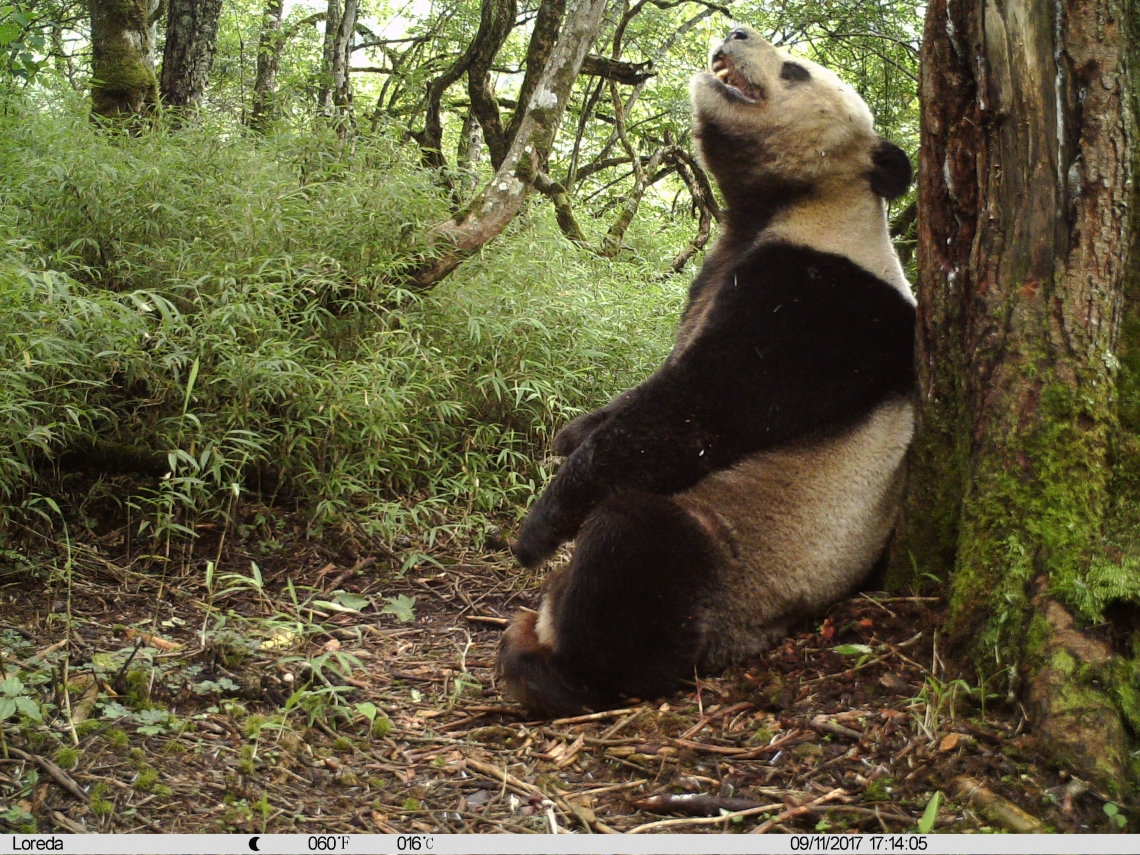

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Anzihe NR_rubbing back on tree_PKU

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_scent marking by handstand_IOZCAS

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wolong NR_scent marking_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Qinling Mountains_smelling scent mark tree_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_scratch marks on scent marking tree_San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Changqing NR_young panda playing_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_tree climbing_IOZCAS

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wanglang NR_on trail in thick bamboo_Sheng Li