Habitats: The panda has the most restrictive habitat requirements among terrestrial bears, occupying broadleaf and coniferous forests with ample bamboo understory. Seasonal elevational migration has been documented for some populations, where pandas move to higher elevations in summer to track the new growth of bamboo, which is most nutritious. While giant pandas show a preference for old-growth, heavily-shaded forests, they readily use secondary growth, especially after sufficient time following logging activities allows early successional forests to mature (but well before reaching old-growth stage).

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Niuweihe NR_mountain habitat in fall_Fang Wang

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_forested mountain habitat_San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_rainy mountain habitat_San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Changqing NR_thick bamboo understory_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_understory habitat_San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wanglang NR_habitat in conifer forest_Sheng Li

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_camera trap photo at water hole_D Wang

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_cave den used for rearing cub_San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

Diet: Giant pandas are bamboo specialists. They are the most herbivorous bear. The majority of their diet (>99%) is comprised of bamboo, supplemented with forbs and, very rarely, scavenged meat. They appear to forage on any bamboo species in their range, which varies with geography and elevation. They prefer to eat new shoots and younger bamboo, which have more protein and nutrients and less undigestible fiber. They eat both leaves and stems of bamboo plants, although preferences between these parts change with season and nutritional value. This diet is relatively low in energy and protein, but the food source is ample and reliable, which is quite different than the other bears, which often rely on foods that change seasonally and may vary drastically in abundance year to year. Many other aspects of their biology and behavior appear to be shaped by bamboo specialization. Notably, the gene that normally promotes taste for meat is deactivated, and they employ many behavioral and physiological strategies for conserving energy (e.g., they select gentle slopes and often walk on trails instead of through thick bamboo).

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Changqing NR_bamboo shoots_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wolong NR_fresh feces with bamboo fragments_Sheng Li

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Changqing NR_feces with bamboo leaves_Sheng Li

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wolong NR_signs from consuming bamboo shoots_Sheng Li

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wanglang NR_walking on trails saves energy_Peking University

Hibernation: Giant pandas do not hibernate. Although the nutritional quality of bamboo declines during winter, bamboo is still abundant, so they remain active in the snow. Even females in birthing dens come out to feed. Besides the year-round availability of bamboo, this food does not enable pandas to put on sufficient fat to be able to hibernate.

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_ Anzihe NR_active in winter because food is available_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Sichuan China_eating bamboo in winter_Sheng Li

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_camera trapped in snow_Peking University

Reproduction: The reproductive ecology and biology of giant pandas is well studied. In spring, several males vie for access to a fertile female, competing fiercely. Pandas rely on scent and vocalizations in the spring to localize and court mates. Pandas have delayed implantation, in which the development of the embryo is arrested for several weeks, yielding a variable gestation period of 84–173 days.

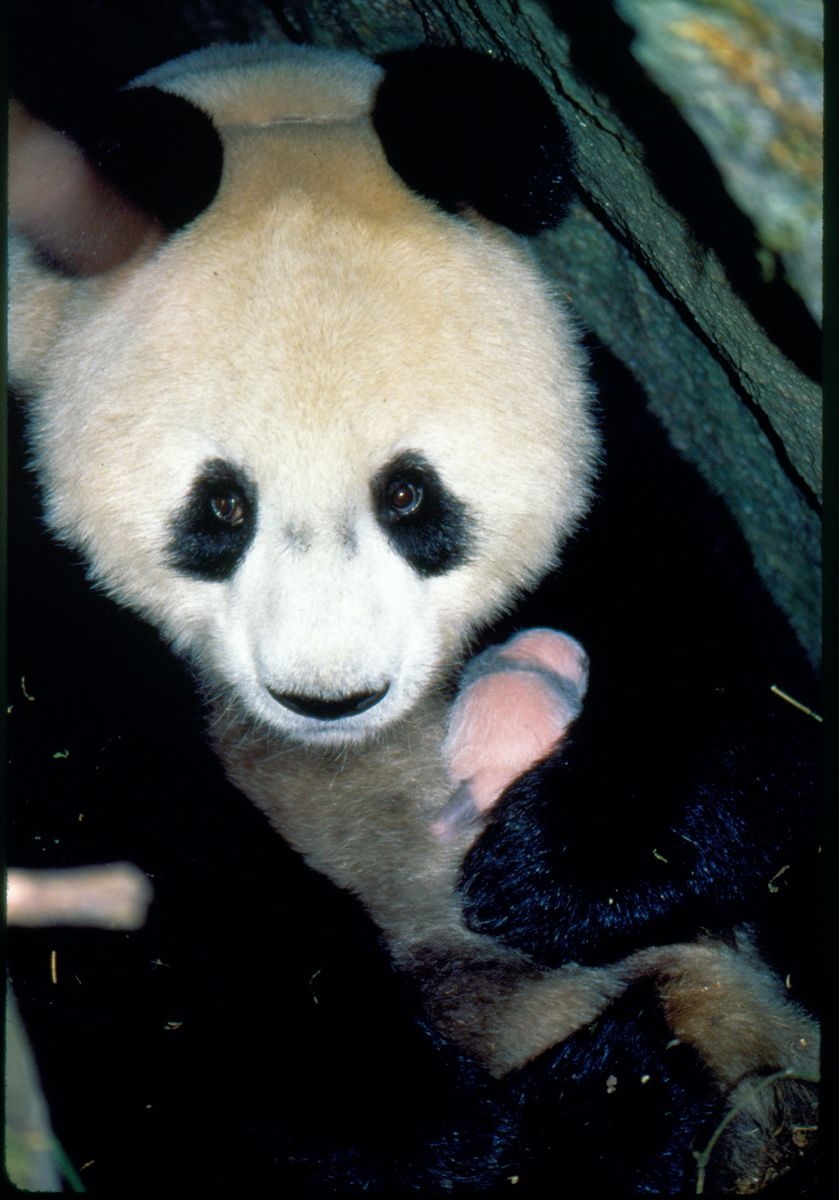

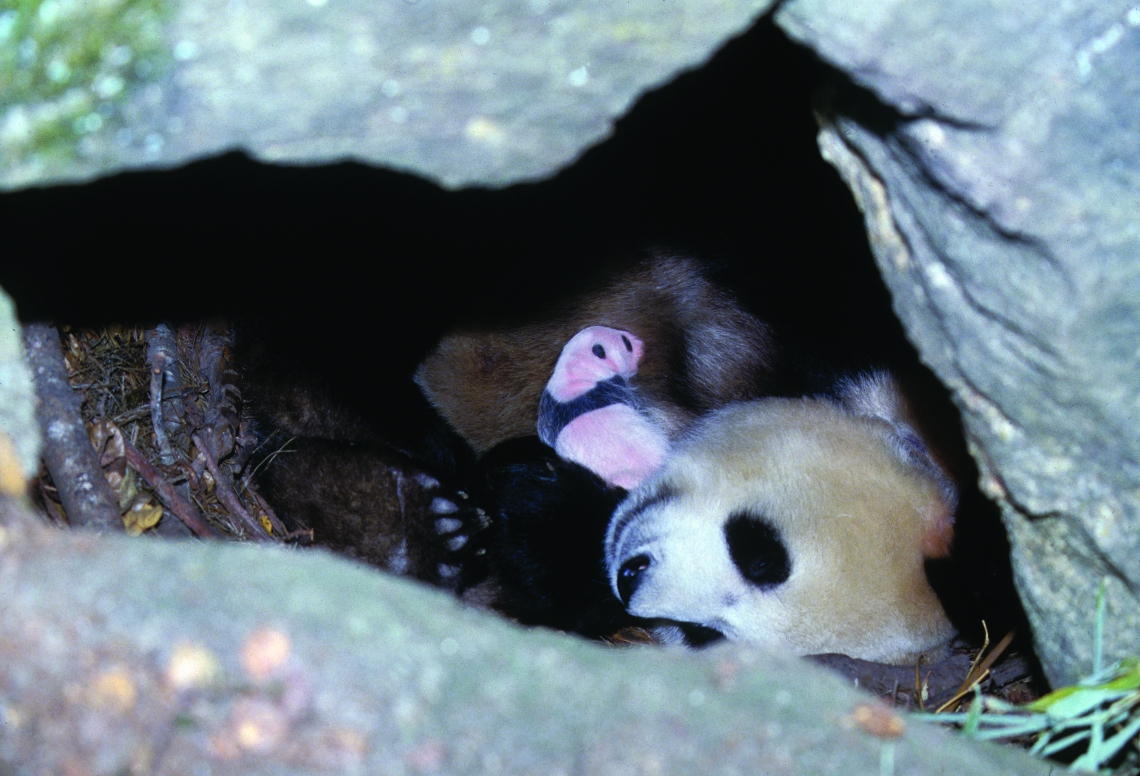

Females give birth to 1 or 2 cubs (rarely 3) in tree or cave dens in late summer and early fall. However, they almost never raise more than 1 cub in the wild, apparently abandoning or consuming the weaker one. They are the only known mammal to purposefully reduce their litter size after birth. Before being relegated to the mountainous habitats where they live today, pandas of the past may have been able to raise twins; today there are rare sightings of pandas accompanied by 2 cubs. Cubs are highly altricial, and the mother:cub weight ratio is greater than that for any other eutherian mammal. Cubs are weaned at 1.5–2 years.

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_estrous female in tree courting male at base_IOZCAS

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Foping NR_mating_IOZCAS

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Wanglang NR_hollow tree used as birthing den_Fang Wang

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Changqing NR_mother with tiny cub in den_Peking University

Giant panda_A melanoleuca_Changqing NR_mother and cub in den_Peking University