Discovering and Naming Bear Species for Science

The purpose of a scientific name is to ensure that each known species has a unique and clear identification. Common names often vary by locality (especially among different languages, but even in English), and also may change through time. Among the 8 bear species, there are unfortunately 2 called “black bears”, one in Asia and one in North America. The most standardized common names for these are the Asiatic and American black bear, respectively. But the Asiatic black bear is also called the Himalayan black bear or Moon bear in some areas, creating potential confusion. The American black bear is typically just called “the black bear”, by both local people and scientists in North America. Since the 2 “black bear” species are on different continents, it is usually obvious which one is being referred to, but if a zoo in Europe displayed a “black bear”, it could be confusing. Likewise, people can become confused over names like grizzly bear, Kodiak bear, and brown bear, which are all North American bears of the same species, but vaguely defined by geographic areas. Scientific naming resolves these problems.

Swedish zoologist/botanist Carl Linnaeus, in his famous 10th Edition of Systema Naturae (1758), created the binomial system of taxonomic nomenclature for animals. He divided the Animal Kingdom into 6 classes, and within Class Mammalia created 8 orders. Bears fell within the Order Ferae (now Carnivora), which also included seals, canids, felids, viverrids, and mustelids.

Even before Linnaeus, there were some species names designated in Latin (the language of science at the time), but Linnaeus’ publication in 1758 marks the agreed-upon starting point for binomial (two-part) scientific names consisting of a genus and species. By convention, the person who first gave the species a binomial name has their name forever linked to that species name. Often, this person (called the authority) is not the real “discoverer” of the species, as local people would typically have known of the species well before that (especially for large, visible species like bears). For example, the French priest/naturalist Armand David is credited with “discovering” the giant panda in the realm of science, although local Chinese people obviously knew of it –– in fact, David first became aware of it when he was shocked to see a skin of one hanging in local person’s home.

One key aspect of scientific naming is that the first-published species name (specific epithet) is assigned forever, based on the “priority principle”. The genus, though, may change, if it is later discovered that the species better fits a different grouping. For example, the generic names of giant pandas, sun bears, and sloth bears were all changed shortly after the initial naming, but their original specific epithets (and the person who created that name) have been retained. Likewise, if a “new” bear species is named, and it later turns out to be one of the already named species, the oldest name prevails. This has occurred many times with bears, most notably with brown bears, which were once divided into nearly 80 separate species in North America alone (by the “father of mammalogy”, C. Hart Merriam in 1918) –– all are now recognized as just one species, under the name first given by Linnaeus.

Page 47 from Linnaeus' Systema Naturae (1758), taxonomically naming bears for the first time.

Linnaeus named only 2 species of bears: one (the brown bear) he called Ursus arctos, meaning "bear" in Latin and in Greek; the second he called Ursus luscus, which is the wolverine (now Gulo gulo, a mustelid). He noted that Ursus arctos lives in the forests of Europe, and hibernates without food. He also mentioned “the great white sea bear of the Arctic”, which he called Ursus maritimus, although he considered it a form of Ursus arctos. He noted that it may be a different species, but he never saw one, so could not classify it as such.

![Brown bears with highly varying coat colorations were a source of confusion as to how many species there were [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25]. Brown bears with highly varying coat colorations were a source of confusion as to how many species there were [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25].](https://globalbearconservation.org/admin/resource/images/eb7bbd362836024a250a76e24688a02d9cbd146a299f97d64d00c64329815d87.jpeg)

Brown bears with highly varying coat colorations were a source of confusion as to how many species there were [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25].

Many different color patterns were observed among brown bears in Europe, some being more common in specific geographic areas, leading to early misperceptions about how many species these represented. Today, none of these are even recognized as subspecies. However, different subspecies of brown bears do occur in North America and Asia, two of which are particularly prominent in history and culture; moreover, even now, both are often misperceived as distinct species by the general public: these are the grizzly bear and Syrian bear.

The grizzly bear is the most widely-recognized subspecies of bear of any species. It is interesting that the actual meaning of the common name of this bear is often confused. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, in their famous expedition of discovery across the western North American continent in 1804–1806, were among the first non-indigenous Americans to encounter this species, in what is now North Dakota (Hearne, see below, saw a skin of one in Canada more than three decades prior). Their party had numerous run-ins with this species along their trek, nicely chronicled in a book by Paul Schullery. In their journals, which contained many misspellings, they sometimes referred to it as the “grisley bear”, and often emphasized it’s ferocity, suggesting that this name may have referred to its grisly reputation.

Lewis and Clark, though, did not provide a Latin name for this bear. That credit goes to the American zoologist George Ord, although his 1815 publication North American Zoology, which brings forth to science many of the species first encountered by Lewis and Clark, actually never mentions Ord’s name, as he was too modest to take credit (although later authors divulged his identity). Ord’s scientific name, Ursus horribilis (now U. arctos horribilis), leaves no doubt as deriving from its “dreadfully ferocious” behavior (which is quite a departure from other bear names, which typically refer to where they live or physical characteristics). Ord never saw a live grizzly bear, but relied on descriptions from Lewis and Clark (whose journals were not yet published) and a book by H.M. Brackenridge, published just the year before. Brackenridge retraced part of Lewis and Clark’s travels up the Missouri River to central North Dakota in 1811. Ord, quoting Brackenridge’s description of the grizzly bear, says: “He is the enemy of man, and literally thirsts for human blood … The Indians make war upon these ferocious monsters … the death of one of them gives the warrior greater renown than the scalp of a human enemy.”

Hemprich and Ehrenberg’s plate of a Syrian bear showed it to be all white, but their text described it as variegated tawny and white.

A strikingly golden-colored bear from the Middle East, appears in some of the earliest written records of bears. It was mentioned a number of times in the Bible, including a mauling incident in what is now the Israel-Palestine West Bank: “There came two female bears out of the woods and ‘tare’ [maul] forty-two of the lads.” This Middle Eastern bear is now often ascribed to a vaguely defined subspecies of brown bear, Ursus arctos syriacus, originally ranging from Turkey and the Caucasus south to Egypt.

The so-called "Syrian bear" was first described for science by Wilhelm Hemprich and Christian Ehrenberg, German naturalists who observed and collected thousands of specimens of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, and plants from Egypt north to Lebanon and Syria during an expedition from 1820–1825. They collected the type specimen of this bear — which they named Ursus syriacus — in Lebanon. Their drawing showed a bear nearly as white as a polar bear, but their text describes it as having a fulvous/tawny–white variegated coat color. Syrian bears were highly sought after because of their strikingly light coat color. A small number of these bears apparently survived in Syria and along the Syria-Lebanon border until about 1960, when they disappeared. However, since 2004 there have been sporadic sightings of bear tracks in southwestern Syria and a video of a bear in Lebanon (near the Syrian border) in 2016. It remains unclear whether there are one or more wild bears living in this area, and if so, where they came from.

Dutch explorer William Barentsz' crew attacked by polar bear in 1596 [color engraving by Johann Theodor de Bry, 1599]

Phipps 1774 description of polar bear, providing scientific name Ursus maritimus

A truly-white bear, the polar bear, was well known to northern European mariners well before they were provided a scientific Latin name by Constantine John Phipps in 1774. Phipps was an English explorer and Royal Navy officer. On one voyage in 1773 he attempted to find a route to the East Indies via the North Pole, but was thwarted by ice north of Svalbard. He published his journal of this voyage, and in one of the many appendices, mentioned animals that he observed, “some which have not before been made public”, and “as modern naturalists [I] have formed the technical terms of their science out of the Latin.” He called the sea bear Ursus maritimus (following Linnaeus), and used the common name polar bear. He says that they were “found in great numbers on the main land of Spitzbergen”, and that his sailors killed and ate them. He notes that this species is “much larger than the black bear”, by which he means the European brown bear, which was sometimes referred to as a black bear before the American black bear was discovered. One individual weighed 610 pounds “without head, skin, or entrails.”

Crude sketch of American black bear in Brickell's Natural History of North Carolina (1735)

A drawing of the American black bear did not appear in Pallas' 1780 description. This fine drawing is from St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25.

Peter Simon Pallas, a Prussian (German ) zoologist, botanist, and taxonomist, named the American black bear, Ursus americanus, in 1780. He traveled, and collected natural history specimens across Russia, but was never in North America. However, he had the opportunity to view some live bears that had been shipped to London, and noted their differences with the European brown bear and polar bear (which he called Ursus marinus). Pallas extensively quotes from a 1737 book by John Brickell, which goes into great detail about how bears in North Carolina were often eaten by European colonists (“the young cubs are a most delicious dish”). He also mentioned that these bears may kill pigs and damage corn (“they generally spoil ten times more than they eat”), “nimbly climb trees” and expertly catch fish. He claimed they commonly have litters of three to five cubs during winter. Brickell never attempted to distinguish bear species, but noted that the bear in North Carolina was not as large as those from Greenland and Russia. A later naturalist, Samuel Hearne, who travelled across northern Canada during 1769–1772, correctly distinguished all three North American bear species: he observed the black bear, polar bear, and saw “the skin of an enormous grizzled Bear” (this being the first published use of this term). Hearne’s account of the American black bear, although based on his earlier journals (nearly a decade before Pallas saw them in captivity), was not published until 1795, 3 years after his death. Hearne provided some interesting observations, such as noting a denning period of at least 4 months, always underground, and seasonal changes in food habits. He mentioned that in June, black bears devoured abundant floating water insects (Mayflies) by swimming with their mouths open “in the same manner as the whales do.” Darwin later referred to this in his first edition of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection: “I can see no difficulty in a race of bears being rendered, by natural selection, more and more aquatic in their structure and habits, with larger and larger mouths, till a creature was produced as monstrous as a whale. (He was ridiculed for this, and removed it in later editions.)

First published drawing of a sloth bear in a science publication, from a captive individual in London, showing shaggy coat. (From Shaw 1791, who copied the drawing from Catton 1788, who called the animal a Petre Bear)

Inside the mouth of captive sloth bear, showing (incorrectly) the absence of all front teeth, leading zoologists to classify it as a sloth. (From Shaw 1791, drawing also copied from Catton 1788)

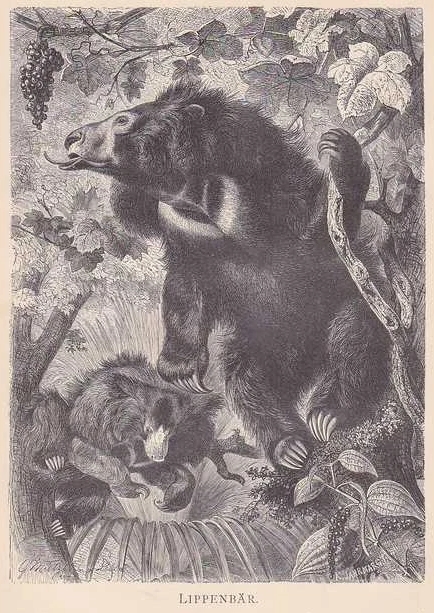

In 1791 George Shaw, an English botanist and zoologist, published the 2nd volume of his Naturalist’s Miscellany, a disorganized set of various species accounts (both plants and animals), accompanied by many colorful drawings. At that time, 3 species of bears were known to science (brown bear, polar bear, and American black bear). He described the sloth bear, but did not consider it to be a bear. He called it the “ursiform [bear-like] sloth” with the corresponding scientific name Bradypus ursinus. He noted that “it has a striking resemblance to the common bear, and has even been considered as a species of bear by some naturalists”, but it’s “peculiar” teeth and claws “forbid it to be any longer considered a species of Ursus.” He said it had no front (incisor) teeth, and provided a drawing of such (this is incorrect, as sloth bears are missing only the 2 front ones on the top). The individual he described was a live, 4-year-old bear from India, taken initially as a cub from a den in the wild. It was tame enough to allow people to touch and examine the inside of its mouth. However, the drawings in Shaw’s book were first published by Catton, so it is unclear if the error concerning the teeth arose from that original drawing, or if this individual really lacked all incisors. Later examination of the skull of this bear by Baron Georges Cuvier revealed that it had tooth sockets for incisors.

For several years after the first scientific naming, there remained much confusion about its taxonomic classification, where it lived, and as a consequence, what its common name should be. It was, for example, called a Lion Monster, a Bearded Bear Badger, and an African Bear Badger. German zoologist Friedrich A. Meyer provided the name Melursus lybius, hearing that in captivity it liked honey, and believing it was from “interior Africa”. A series of authors renamed the species many times, both the genus and species. One author asserted that the missing front teeth –– which fooled many others into thinking it wasn’t a bear –– was due to being pulled by Indian bear-tamers (from where all the specimens came from), and therefore considered it to be a real bear, calling it Ursus labiatus, the Lip Bear. But since Shaw’s specific epithet has precedence due to the principle of priority (even though he thought it was a sloth), and since Meyer’s generic name is the first to be called a bear (and most modern biologists still think it should not be in Ursus), the combined name becomes Melursus ursinus, which translated is a bit odd: the honey-bear bear.

First published drawing of a sun bear, from a Sumatran bear shipped by Raffles to a museum in London in 1820. (From Horsfield 1824)

First published drawing of a Bornean sun bear, showing wide "quadrangular" chest marking. (From Horsfield 1825)

The sun bear is often thought to be named for the marking on its chest, which may look like a sun in some individuals. However, it was not initially called a sun bear. At first, 2 species were described. The first was a live individual, taken as a cub from the wild in Sumatra, and kept by Thomas Stamford Raffles as a pet for 2 years. In 1821, Raffles published a paper where he gave it the name Ursus malayanus, and described some of the pet bear’s behaviors and also mentioned its small stature, short hair, and a “large heart-shaped spot of white on the breast.” He sent another dead specimen to the Museum of the East India Company (London), where Thomas Horsfield was able to study it. In 1824, Horsfield published a detailed account, where he described the chest marking as “nearly represented by the letter U”. He specifically distinguished this bear, which he called “Bruang [bear] of the Malays” from the “Bear of India”, which by this time was accepted as a true bear (sloth bear, then called Ursus labiatus). In 1825, Horsfield published another paper, this time describing a pet bear taken from Borneo. He commented that “even to a superficial observer” this new bear “is very nearly related to Ursus malayanus,” but he nevertheless considered it a distinct species. He gave it the generic (or subgeneric) name Helarctos because it lived near “the hot sun”. Horsfield noted that the “bear from the Island of Borneo” was distinguished from the Sumatran “Malay bear” by having a “more vivid and nearly orange” chest patch. He described it as “quadrangular form” and gave it the specific name euryspilus, which means wide birthmark (hence, not like a sun). At this time, Horsfield commented that there were 10 other species of bears. We now know that there are just 8 bear species, including 1 that is commonly called the sun bear (or Malayan sun bear), Helarctos malayanus, although the Bornean form is considered a distinct subspecies, H. m. euryspilus.

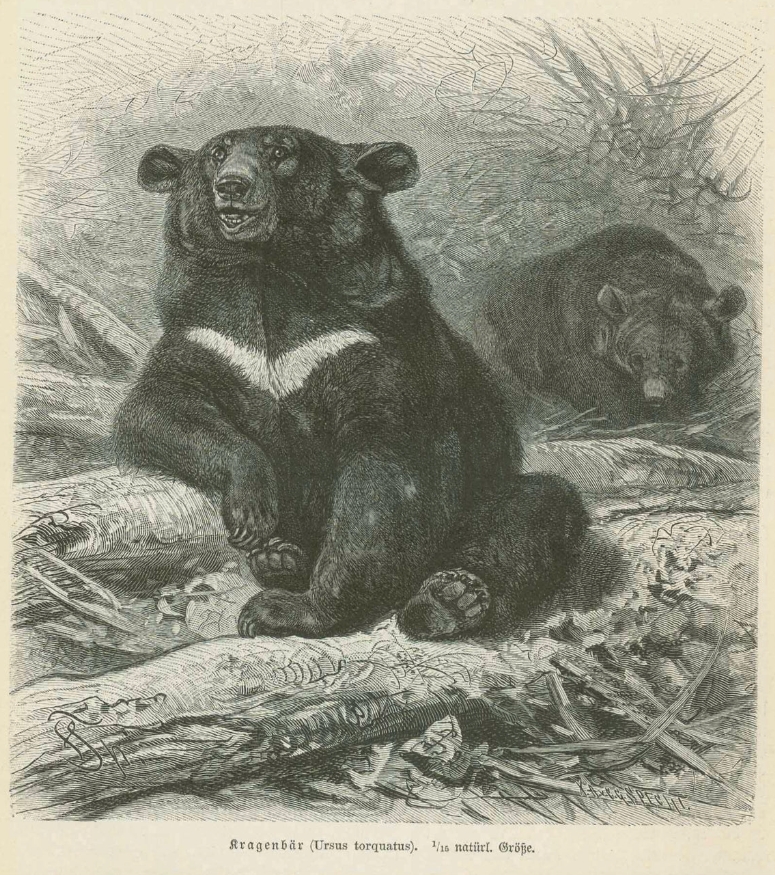

![The Asiatic black bear was originally called the Thibet bear because it was thought to have a narrow distribution. [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25, though named the year before by G. Cuvier] The Asiatic black bear was originally called the Thibet bear because it was thought to have a narrow distribution. [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25, though named the year before by G. Cuvier]](https://globalbearconservation.org/admin/resource/images/26c8ebd4c76c11db8e4df870269582f7d9ca234b6793ca679b9c5e56a5915c7e.jpeg)

The Asiatic black bear was originally called the Thibet bear because it was thought to have a narrow distribution. [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25, though named the year before by G. Cuvier]

Zoologists of the early 1800s began to recognize that India had at least three black-colored bear species. One notable French naturalist and collector, M. Alfred Duvaucel, who had observed all three (in fact, helped obtain Raffles’ sun bear specimen), described a bear that lived in the mountains of Sylhet (northeast India); simultaneously the botanist Wallich reported seeing this bear in Nepal. Baron Georges Cuvier officially named it Ursus thibetanus, or “the Tibet bear” in 1823 (later renamed Asiatic black bear when its wider distribution became known).

The scientific name of Asiatic black bears was, for a period, changed to Ursus torquatus, in reference to its white collar or necklace. (From Brehms Tierleben 1890)

This bear was considered “particularly remarkable by the thickness of its neck” (presumably meaning the ruff of hair around the neck), large ears, and relatively short claws (compared to the sloth bear), from which it was initially assumed that it was a poor climber (an incorrect assumption – in fact, the Asiatic black bear is a much better climber than the sloth bear). It is most curious that the early descriptions of this bear mention but do not draw special attention to the broad white crescent on the chest, which is certainly a distinguishing characteristic of this species (and quite visible on the first published drawing of it, above, and later drawings, right).

Ironically, the sloth bear (above) (referred to as a Lip bear in this drawing) has a very similar crescent-shaped white chest marking as the Asiatic black bear, often leading to confusion in species identification. (From Brehms Tierleben 1890)

Less than 20 years after the scientific naming of the Asiatic black bear, Wagner (1841) proposed changing the scientific name from Ursus thibetanus to Ursus torquatus, because, they claimed, the species did not occur in Tibet, so the original name should be invalid (it actually does occur there, but very little). The Latin specific epithet torquatus means “adorned with a neck chain or collar”, referring to the prominent white chest marking on all individuals. This name was retained for half a century. (Note that the first global range map for bears, published by Grevé in 1894, used the name U. torquatus.) However, through time this name was rejected, and thibetanus (however odd) was restored due to the priority principle.

![The first (live) scientific specimen of an Andean bear was reportedly obtained in Chile, where it does not naturally occur. [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25] The first (live) scientific specimen of an Andean bear was reportedly obtained in Chile, where it does not naturally occur. [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25]](https://globalbearconservation.org/admin/resource/images/e8bca81a469df6ab6007ae1d4465957b186ccace20c6fe69f6261fa0d068e31f.jpeg)

The first (live) scientific specimen of an Andean bear was reportedly obtained in Chile, where it does not naturally occur. [From St.-Hilaire & F. Cuvier 1824-25]

In 1825, Georges Cuvier’s younger brother, Frédéric Cuvier had an opportunity to examine the first scientific specimen of an Andean bear, which had been brought to the menagerie of the Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris, where he was the head keeper. Cuvier mentioned that “it had been brought back to Europe by one of the King's ships which had acquired it in Chile; thus its origin is not in doubt” [translated from original French]. However, the circumstances by which it had been obtained are not reported (the species has never naturally ranged into Chile, but it is possible that a captive animal was purchased there). The bear was transported alive, but Cuvier reported that it was a young bear, weakened by the trip, and could not be kept alive. He gave it the name "bear of the mountains of Chile", and because of the prominent circles around the eyes, provided the species name “ornatus”.

Père Armand David's church, Sichuan China [photo D. Garshelis]

The last species of bear that became known to western science was the giant panda. This is not surprising, as this species existed only in a remote, very mountainous part of central China. A French Lazarist missionary, Père (Father) Armand David was stationed in China from 1862–1874 to spread Christianity, but at the same time, was on a natural history collecting mission. He sent massive numbers of plant, insect, and animal specimens back to the Museum of Natural History in Paris to enter the scientific collection. He also kept a detailed diary, which was translated from French to English by Helen Fox in 1949.

![Armand David’s (1869) brief description of the giant panda, noting it’s size and coat color, which he says is the “prettiest of the genus [referring to Ursus] that I know”. Armand David’s (1869) brief description of the giant panda, noting it’s size and coat color, which he says is the “prettiest of the genus [referring to Ursus] that I know”.](https://globalbearconservation.org/admin/resource/images/ae0b9fcbb1d483ccfd2bdb6f485c3bb2bc3d247469cbcb1c6254bdd142e343af.jpeg)

Armand David’s (1869) brief description of the giant panda, noting it’s size and coat color, which he says is the “prettiest of the genus [referring to Ursus] that I know”.

In February, 1869, David travelled to the mountainous Muping area of Szechwan (now Sichuan Province) in central China. He was invited to have tea in the home of a local, where he saw the skin of a “white and black bear”, after which he asked his hunters to obtain a specimen for him. Within 2 weeks they captured a young female alive, but ended up killing it for transport. He wrote in his diary: “this must be a new species of Ursus, very remarkable not only because of its color, but also for its paws, which are hairy underneath”. A few days later the hunters brought in a dead adult, and then a week later a live panda (i.e., red panda), and David commented that “its paws and head exactly resemble those of my white bear.” He sent the specimens to Alfonse Milne-Edwards at the museum in Paris, and his accompanying letter was published as the first scientific description of this species, which he named Ursus melanoleucus [black and white bear].

![First drawing of giant panda published in a scientific journal, based on the specimen sent to Paris by Armand David [from Milne-Edwards and Milne-Edwards 1868 to 1874, plate 50]. First drawing of giant panda published in a scientific journal, based on the specimen sent to Paris by Armand David [from Milne-Edwards and Milne-Edwards 1868 to 1874, plate 50].](https://globalbearconservation.org/admin/resource/images/f4a385640d98782e23aad141341f25ef986d87713b5bf6774bab88513dfcfaea.jpeg)

First drawing of giant panda published in a scientific journal, based on the specimen sent to Paris by Armand David [from Milne-Edwards and Milne-Edwards 1868 to 1874, plate 50].

![Hairy underside of feet (anterior, right) of first specimen of giant panda sent to Europe. [Milne-Edwards and Milne-Edwards 1868 to 1874, labelled Ailuropus instead of Ailuropoda]. Hairy underside of feet (anterior, right) of first specimen of giant panda sent to Europe. [Milne-Edwards and Milne-Edwards 1868 to 1874, labelled Ailuropus instead of Ailuropoda].](https://globalbearconservation.org/admin/resource/images/688a235a0df57bf8d167a0449a0a33063af3d84f3828597862366433e661795e.jpeg)

Hairy underside of feet (anterior, right) of first specimen of giant panda sent to Europe. [Milne-Edwards and Milne-Edwards 1868 to 1874, labelled Ailuropus instead of Ailuropoda].

After examining the specimen in Paris, Alfonse Milne-Edwards wrote: “By its external form, it indeed resembles a bear very much, but the osteological characters and the dental system clearly … brings him closer to pandas and raccoons. It must constitute a new genus which I called Ailuropoda" [meaning 'panda-foot']. Milne-Edwards published a color drawing, and also drawings of the feet and skull. Notably, he considered the feet like that of the red panda because of the hair on the underside; he did not mention the “pseudo-thumb”, which is actually the character of remarkable convergent evolution between these two species that, for many decades (before modern genetics), led scientists to believe that the giant panda was not an ursid. Whereas Milne-Edwards is credited with the genus name, David's name remains the authority for this species (although changed to melanoleuca to match the new feminine Latin name of the genus). One interesting sidenote is that David sent some live animals to Paris, including a new deer (Père David’s deer, Elaphurus davidianus), and in the introduction of Helen Fox’s translation she suggests that he also sent back a live giant panda: “but the first to come did not long survive its transference from the mountains of Szechwan.” It remains a source of confusion as to whether David actually sent a live giant panda to Europe.